This is Puppis A, a supernova remnant seen through a gap in a large foreground nebula, the Vela Super Nova Remnant. If you're a longtime reader of the astronomy posts here then you probably realize that this is not the way nova remnants are supposed to look.

Look how fragmented the red clouds are, as if they were torn to pieces by an angry giant. Not only that but the blue pieces of the cloud are long and fibrous, and the pieces are parallel...not the shape you'd expect in a conventional explosion. One of the red clouds on the right has a corkscrew shape. So what gives here? I don't know.

Do you suppose there was one big explosion then ejected fragments blew up in secondary explosions the way some fireworks do? I'm probably wrong.

It's a violent place with (I'm guessing) cumulative solar winds of an intensity that's hard to imagine. Maybe we should be surprised when any remnants have a normal shape in a rough neighborhood like this one.

Back in our neighborhood, here's (above) the familiar Crab Nebula, looking better than you've ever seen it before. The star that created it went nova in 1054 AD. When I was a kid a local science museum sold black and white glossies of this object and I bought one. It looked like a simple doughnut with slightly fuzzy edges and a star in the middle. Now, with aid of the Hubble, it looks like an explosion in a cat fur warehouse.

The rapidly enlarging cloud is now 10 light years across.

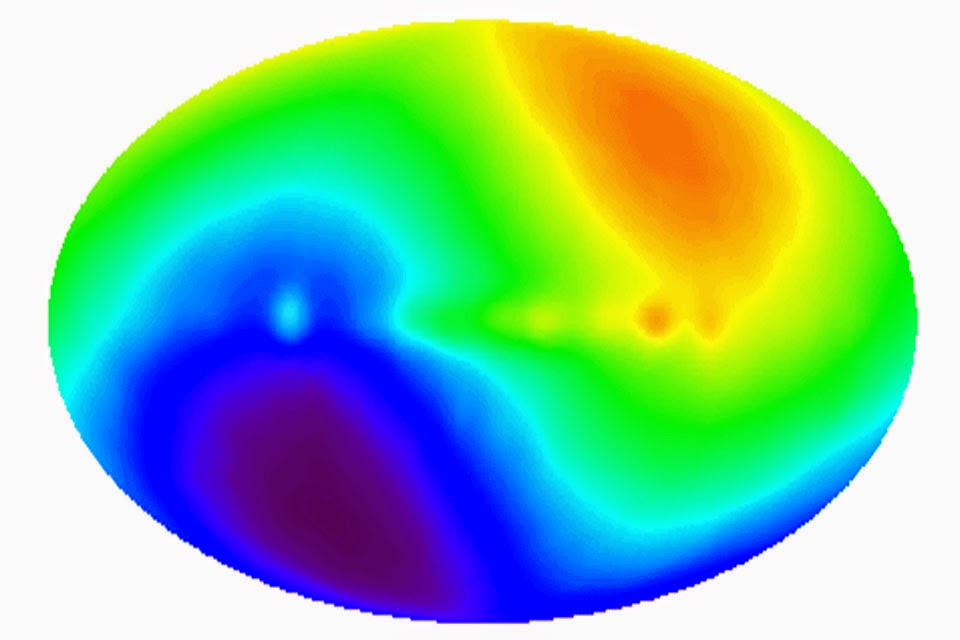

Above, a color enhanced Pluto as seen by the New Horizons spacecraft in July. The probe is now headed for an asteroid in the Keiper Belt. It's a billion miles more remote than Pluto.